Monday, October 13, 1930, the last of the Columbus Day weekend, was unusually warm on the Cape, with the temperatures running up to 90°. But in Yarmouth Port it became considerably hotter that day – so hot that the telephone poles burned. About 9:45 that morning young Henry D. Hart came running into Hallet's store in Yarmouth Port, and told his friend Matt Hallett that he could see smoke – something must be on fire. They both jumped into Matt’s Hudson and drove eastward on Main Street to a point opposite the library, where they discovered that the residence of Dr. Henry B. Hart (young Henry's home) was ablaze.

Dr. & Mrs. Henry B. Hart

The fire seems to have started in the laundry and everyone available came to the scene, doing their best to salvage the contents of the house, carrying out the doctor’s records, the silverware and everything else portable until heat became too great. Despite the efforts of the Hyannis, Falmouth, Harwich, Brewster, and Dennis fire departments, before the day was over, Dr. Hart's house and garage were destroyed, as was the vacant next-door home and barn of Franklin Arey, while the barn on the other side belonging to Seth Taylor was charred. The Yarmouth Register reported the following Saturday that even the telephone poles caught on fire. Only a favorable wind kept the fire from spreading further.

Every well and cistern in the area was pumped dry and, the tide being low, seawater was not available until the Dennis Fire Department ran a hose some half mile to the ocean and arranged a string of pumping engines to bring salt water up to the scene. Yarmouth at that time had no fire department and no water department.

The following Saturday, Mr. Joshua Howes of the Barnstable County Mutual Fire Insurance Company and a resident of the village, called a meeting at Lyceum Hall to discuss and consider the question of water supply and fire protection within the town. An article had been in the town warrant for each of the last 15 years for the establishment of a fire department and each year it had been voted down. After this disaster, however, a special town meeting was called on Saturday, December 13, 1930 and the citizens promptly voted $75,000 for a water system and $17,000 for fire apparatus.

The 2 1/2 miles of water main, in addition to the pumping station and water tower, were for the north side of the town only. People on the south side said they had plenty of water and didn't need water mains. It was only after World War II that the water mains were extended from the pumping station across Union Street/Station Avenue to Route 28 and the south side of the town had a municipal water system.

Mr. Howes, Frank L. Whitehead, and U. Frederick Stobbart contracted for the purchase of two 500 gallon Maxim fire trucks – one to be located on the north side of town and one on the south side. On January 13, 1931, the first truck arrived at South Yarmouth and was housed in Ernie Baker's garage and the fire siren was placed on top of the garage. Gilbert Studley, appointed chief engineman of Company #1, called the first meeting on February 3, 1931, with 18 members present.

South Yarmouth’s Maxim engine.

Shortly thereafter, the second engine was delivered to the North Side and Fred Stobbart, appointed chief engineman of Company #2, organized his crew. The first meeting of Company #2 occurred on May 5, 1931 at the rooms of the Cape Cod Central Club – the two-story building at the corner of Union Street and Route 6A. Their engine was housed directly across the street at the gas station garage then owned and operated by Hemon Rogers. The whistle, again, was placed on top of the garage. Members of the original company included Richard Ellis, Ira Thacher, Sam Thacher, William Marshall, Fred Schauwecker, Arthur Jenner, Norman Cahoon and Granville “Granny” Chalke.

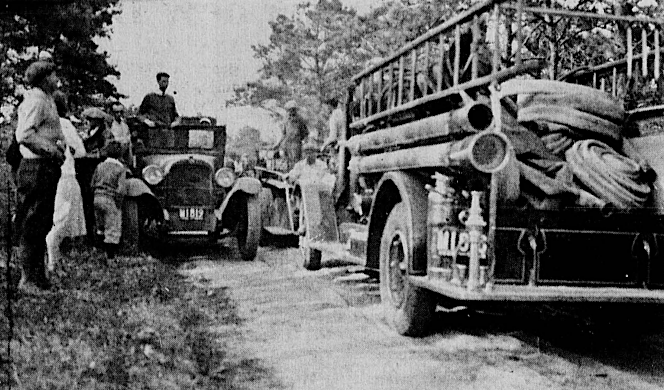

Yarmouth Port’s Maxim engine and other equipment at a fire.

Thus [90] years ago, after a $60,000 (1930 dollars) disaster, the Yarmouth Fire Department was born, and in October of that year the insurance rates adjusted. Two technical notes might be added here. First, for many years the two companies operated completely independently of each other. Although they cooperated on fighting fires, and in fundraising events, they were two separate entities and it was a great deal of friendly rivalry as to equipment and performance. Secondly, Yarmouth never had a true volunteer department where the men donated their services to extinguish fires for the benefit of their neighbors. Yarmouth firemen were paid from the very beginning for every alarm they answered and every hour they worked at a fire. Although they donated many hours of their time for practice, and for improving the equipment, the payments for firefighting made them what is known as a "call" department, hired by the town when called by whistle.

The northside garage where the truck was first stored. Note the fire whistle on the roof.

The first alarm system consisted of telephoning and blowing the whistle to let the firemen who were at work know in what area the fire lay. On the North Side, the signals were one long blow for Yarmouth Port, two long for Yarmouth (east of the Congregational Church), three long for out of town, and too short for fire all out. In South Yarmouth, the whistle blasts ran up to six and woe be to anyone who couldn't count. The buttons to blow the whistle were located in various firemen's houses and one eventually was placed in the living room of Antonio Santospirito, a non-firemen but loyal contributor, who ran the Village Store and volunteered to blow the noon whistle.

Tony Santospirito and his wife.

The telephone alarm system was a phone tree, with the Chief’s number listed in the book, and the chief's wife calling a few men, whose wives in turn called other men. In addition, the telephone operator (it was a hand crank system at the time) had a list of all of firemen and would call as many as possible from the switchboard, generally located in her front room.

Once the town had done its duty of buying the two trucks, some hose, and a few rubber coats and hats, the two companies were pretty well on their own. They raised money by holding dances, card parties, beano, suppers, and food sales, the proceeds of which were turned into improving their equipment. During the first year of operation, Company #2 bought three more coats and hats, ax handles, and three gas masks at a cost not to exceed five dollars each. In addition, both companies expanded their rolling equipment. The records of Company #1 indicate the purchase in 1931 of a "wooden" truck (presumably meaning a wooden body) which was fixed up as a second piece of apparatus and is recorded as having responded to many fires. On the North Side, Company #2 turned a Model T into a chemical tank truck, and obtained a Rio laundry truck with over 100,000 miles on it at the time of acquisition - a 1932 Ford which was made into a brush truck, and another Ford which was converted to a tank truck. In addition, they wrangled a horse-drawn trailer from the Barnstable department, which they used as a ladder carrier behind Chief Stobbart's Ford roadster. They also purchased a gallon of "caron oil" (equal parts of linseed oil and lime water) which was carried on the truck and used to rub on burns.

Although the engines for Company #1 were for many years stored in the same place, the North Side men were very quickly faced with finding a firehouse. Soon they converted an old schoolhouse located almost precisely where the present fire station in Yarmouth Port is now. Here again most of the work was done by the members of the company – much of it volunteer but the records do indicate several of the firemen being paid at the rate of 65 cents per hour.

The first northside fire station - in an old schoolhouse.

From the beginning the two companies responded to an assortment of alarms – chimney fires, brush fires, auto fires, "overheated stove pipe shoved through the roof,” fires at the dump, and on July 21, 1933, the house of John G. Sears was struck by lightning. About $50 damage was done to the M. E. Church "caused by a cigarette dropped on the roof" and $200 damage to Theodore Frothingham's house caused by upset candles. Over on the north side of town, an icehouse insured for $2000 was destroyed and, on at least one occasion, part of John Hinckley & Sons lumberyard burned.

North side station.

But some of the most spectacular fires in those days, as well as the most difficult and arduous to fight, were the forest fires. Chief Dana Whittemore once commented, "if you think there are no woods left on Cape Cod, just fly over it." Nevertheless, modern communications equipment, as well as airplanes and lookout towers, made it possible to locate fires in the woods as they started, and pinpoint the advance of the fire so that equipment could be used to best advantage. In the old days, men and trucks gathered at a predeterminded location, then were dispatched to where the fire was when last reports came in. Many times the head of the fire, so essential to extinguish, was far ahead of the reports, and trucks would be posted along intersecting roads to wait for it to appear.

A West Yarmouth forest fire in the late 1930s

Not to be forgotten are the firemen's wives, who for years drove their cars to the fires, bringing food, fruit, and soft drinks and coffee to the men. The merchants of the town were most generous in donating in these emergencies – during one very smoky house fire Tony opened the Village Store around 2 AM to provide milk (which induces nausea under these circumstances, which expels the smoke from the men's lungs and stomachs). This do-it-yourself fire department continued until long after World War II, with the men fabricating their own equipment. Occasionally the town would help, as in 1938-39 when they agreed to spend $875 for a chassis if the firemen would match it from their own treasury.

The “Fire Belles” during Fire Safety Week, October 1966

In February, 1950, it was voted at town meeting to establish a town fire department, and Gilbert Studley, a charter member of Company #1 was named permanent full-paid Fire Chief with Ira Thacher as deputy. Under Chief Studley and his successor, Chief Dana H. Whittemore, the department was thoroughly modernized. New trucks were bought and new fire stations were built, including one in West Yarmouth, and a salaried complement of chief, deputy, captain, lieutenants and firemen man headquarters at all times. This is the modern department you see today.

Written by Charles A Holbrook Jr. in the 1970s.

Fire Prevention Week, 1966.