The arrival of the first automobiles on America’s roads in the early twentieth century fundamentally changed everyday life on Cape Cod. For residents and tourists alike, motor vehicles opened a path to faster, easier and more pleasant journeys than were previously possible by ship, coach or train.

In 1901 a first ‘around-the-Cape’ trip was accomplished by two friends aboard a red, steam-powered Stanley Steamer car. The automobile owner was Charles Lincoln Ayling, a Boston resident who spent summers in Centerville. His was one of just 600 cars registered in Massachusetts in 1901. He and William Morgan Butler left at dawn and returned home by dusk next day. That 36 hour dash led north to Old Kings’ Highway (now Route 6A), northeast to Provincetown then back along what is now Route 28.

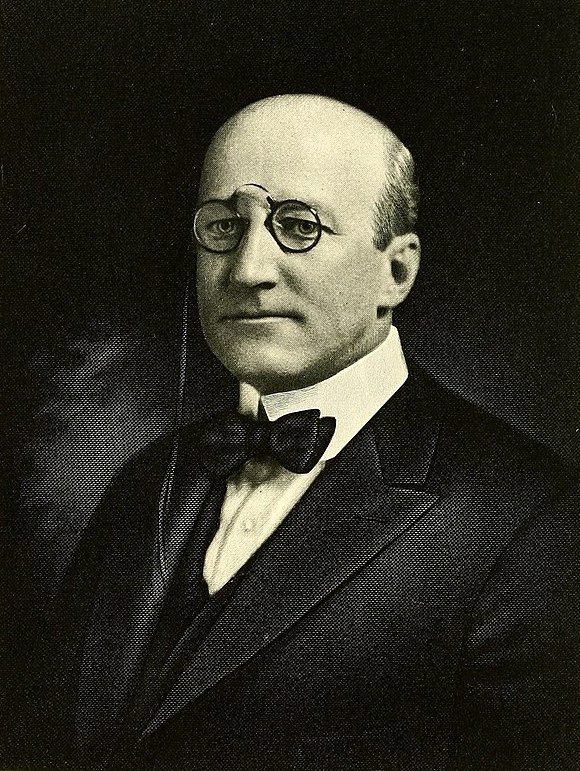

Charles Ayling as a young, then older man

Subsequently, Ayling was to claim (with the backing of others) that his was the first-ever round trip by car to span the full length of the Cape. He later would achieve success as businessman and philanthropist, well-known on the Cape as a benefactor of Cape Cod Hospital, the Centerville Historical Museum, and a founder of the Hyannis Airport, among other things.

The Main Streets of Yarmouth Port, Dennis, Brewster and other villages were described at the time as well-curbed, incorporating lengthy strips of macadamized surfaces while being shaded by fine trees. These roads offered striking views of quaint houses, neat farms, cranberry bogs, marshlands and pristine local waters. However, beyond downtown areas roads typically were unpaved and blighted by deep ruts engraved into their surfaces. These had been formed by grinding of the wheels of the endless flow of carts, wagons and coaches. Unfortunately, these permanent ruts or tracks were some 6-to-12 inches further apart than the standard gage adopted for automobiles. This caused a problem for Ayling’s companion who was forced to spend hours in discomfort, perched at an awkward angle with his head way above that of the driver!

Nevertheless, the 1901 vintage ‘Steamer’ made a 15 mph average and at times hit 30 mph even on rough roads. The vehicle was a big hit among early car owners, who on account of its odd shape, affectionately named it ‘The Flying Teapot.’ It had a gas-fueled boiler under the front seat to generate steam, then transferred energy to the rear axle to power the car. The chassis was wood.

But the ‘Steamer’ could also be a travelers’ nightmare, especially on roads that were rutted, winding, hilly and plagued by sand build-up. So Ayling’s progress was punctuated by lots of slowdowns and even dead stops.

The greater challenge came upon reaching the Outer Cape where roads had been labeled by a travel guide as ‘worst in State.’ Old maps show that these roads faded into a spider’s web of tangled, narrow trails. At this time auto service providers on the Outer Cape were pretty much non-existent.

Ironically, progress in other means of transport had exacerbated the wretched state of Outer Cape roads. Steam ships gave the region access to the outside world by providing reliable packet and ferry services and the Cape Cod Railroad had stretched all the way to P-town by 1873. Both advances undermined the incentive to improve Outer Cape roads and left the area poorly prepared for the emergence of autos.

A hardship for ‘Steamers’ was an insatiable thirst for water, necessitating many refills once initial supplies were gone. Luckily, drinking troughs for horses existed in most villages, making it easy for car drivers to refill their radiators.

Obtaining gas was another hurdle, so long-distance drivers had either to carry gas cans or bargain for fuel from local businesses (e.g. painters, hardware stores) that held stocks for their own use and tires of early cars were troublesome due to their smooth, no-tread design. Ayling was forced to make time-consuming tire changes and patch-fixes several times during the trip.

Another obstacle was that at various points Ayling found himself stalled by a curious, excited yet fearful crowd of onlookers, many of whom had never before seen a ‘horseless carriage.’ He also found himself blocked at times by horse-drawn vehicles passing from both directions. This required one of the men to get out and to cajole nervous horses on their way.

Despite everything, at dusk some 12 hours after his departure, Ayling arrived in P-town only to be greeted by the Town Crier. Bearing a flag and clanging a bell, this official guided his visitors through an enthusiastic throng and on to Gifford House, a local lodging place.

But the proprietor had one final surprise for Ayling: he was worried that his guest’s ‘steam dragon’ might be too great a fire hazard for it to be parked in the inn’s courtyard. This decision forced our travelers to scurry around and find an abandoned barn as the haven for the little red ‘Steamer’ for the night.

Gifford House

Excerpted from an article by HSOY member Bob Leaversuch

Do you love Yarmouth history? Become a member! The first year is free.

1902 Stanley Steamer.